The Eighth Circle

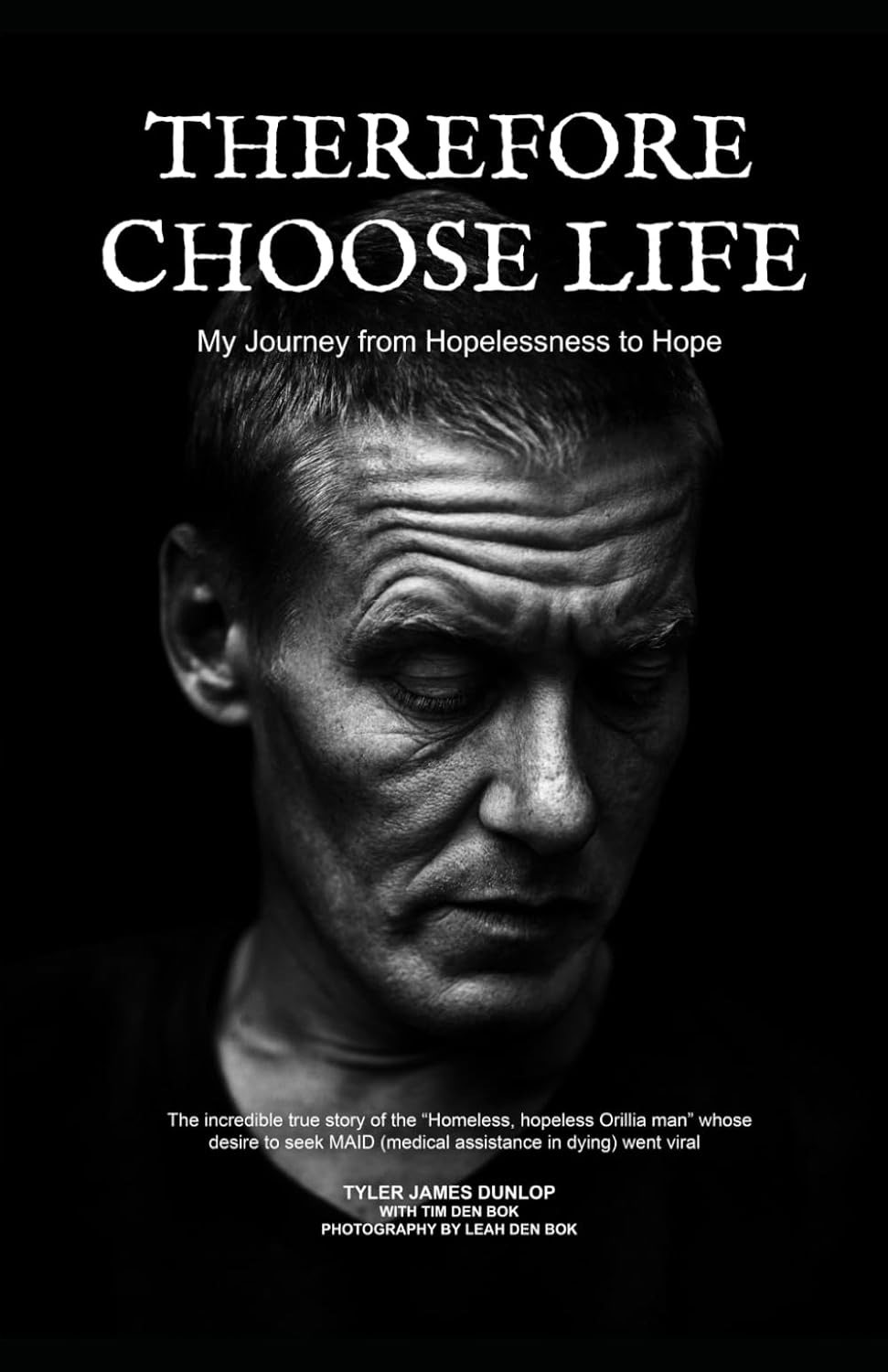

A review of Therefore Choose Life: My Journey from Hopelessness to Hope by Tyler Dunlop

The backstory to Tyler Dunlop’s book Therefore Choose Life reads like a horror show. Dunlop grew up in a broken home, lost his parents when he was young, was diagnosed with schizophrenia, and took up drinking and drugs in high school and couldn’t quit. Homeless, he traveled across Canada, living on the streets of most major ports of call and dozens of small towns in between, and eventually ended up back in Orillia, Ontario, where he grew up. He was homeless there, too.

While wasting away in Orillia, Dunlop wrote to the local newspaper to say that he wanted the government to kill him. As a homeless person with a drug addiction and mental illness, he felt entitled to MAID. (MAID means “Medical Aid in Dying,” a euphemism for euthanasia, or doctor-assisted suicide.) The newspaper reported Dunlop’s story, and to the surprise of his readers of his book—and probably to Dunlop himself—he found a friend in Tim den Bok, who gave him a place to stay, put up with the madness swirling around Dunlop, and helped him to write Therefore Choose Life, now a bestseller on Amazon.

In this short book, Dunlop parallels the depravity of life at the fringes of society to Dante’s Inferno. The comparison fits. In the eighth circle of Hell, Dante encounters sinners who live in a pool of feces. Surrounded by flatulence and drinking the sewage, the damned complain about their lives and fight with each other.

Dunlop’s experience with homelessness sounds about the same. Shelters reek of filth and rage with insanity. The grime of the streets—the drugs, the garbage, the abuse, the degradation—comes through the page thanks to Dunlop’s visceral detail. It’s exactly what anybody who has wandered Canada’s major cities has seen for themselves, but worse.

These details, though shocking, are not the most compelling parts of the book. The most absorbing passages reveal what it’s like to be invisible—what it feels to have somebody look at you but not see you. In one anecdote, Dunlop receives an invitation from a cousin to spend Christmas with her, but she waits until he leaves the room before she takes the family photo. Mostly he’s ignored, and when he’s noticed, he’s not welcome. In another scene, Dunlop wanders into a church to pray only to have ushers follow him around and evil eyes drive him out.

Therefore Choose Life is a litany of failures. Dunlop was failed by his broken family; by his bad health and his own bad decisions; and by public policies that told him in so many ways that his mad, drug-addled, impoverished life wasn’t worth living. The root of most of these failures, Dunlop writes, is a confusion about the difference between liberty and license: “whereas license means the freedom to do whatever one pleases, liberty means the freedom to do what one ought to do. Liberty in other words is not unlimited. We’re not free to do whatever we want.”

Proponents of the weird strain of authoritarian-libertarianism now posing as liberalism in Canada will want to ask Dunlop why they can’t do whatever they want. Why can’t they define words however they like? Why can’t they make “healthcare” mean whatever they want it to mean? As Dunlop explains in anecdote after anecdote, the infernal environments he called home are products of a society that feels it is better to let people suffer in their own depravity than to help them live meaningful lives. In modern Canada, people are left to their own suicidal madness—they are free to choose self-destruction—and most people are okay with that. They vote for it.

As for getting off the streets, that too seems impossible. The cost of housing is becoming unaffordable for many fully employed Canadians, and for people like Dunlop, who have no credit, no job, no family to speak of, and no guide, climbing up through the circles of Hell is an extraordinary challenge.

Here, government appears to have a role to play in helping people right themselves, but as Dunlop documents, many government-funded services fail miserably. At every turn, Dunlop runs into bureaucratic obtuseness. He calls an unstaffed suicide hotline and receives a voice message promising that somebody will call back in two days. His advocates try to enroll him in rehab programs, but the wait times are months long, and red tape makes these programs nearly impossible for him to access.

The medical system can get a person vaccinated in a parking lot with military efficiency, but they can’t or won’t help the person get off their addictions, find them a room to sleep in for the night that isn’t crawling with lice, or deliver the medical procedures a person needs in a timely fashion. But—no pressure—your healthcare practitioner can offer MAID at no charge to you.

As the title of the book—a line from Ecclesiastes—indicates, Dunlop chose life. Early in the book he explains how he came to realize the folly of killing himself. Death isn’t the solution to the problems of life. The solutions Dunlop found are few but effective. One, the most prominent in the book, is his Christian faith. Dunlop writes at length about his relationship with God and the hope he places in salvation.

The other solution is a friend. The cure for loneliness is another person, and Dunlop has found friends in Barbara Diane Fitchette, who met him first on the street and who wrote the introduction to the book, Tim den Bok, who gave him shelter and attention, and others who have been sponsoring his recovery. They are the good people who helped Dunlop see the good in himself.

Therefore Choose Life is available through the Euthanasia Prevention Council.

Robert Grant Price is a university and college lecturer and writer. Expressed is an occasional mailing of essays, stories, and reviews.